It is over 150 years since the Elementary Education Act of 1870 was passed. The Act, known as Forster’s Education Act was named after its sponsor, William E. Forster (1818-1870) the educational reformer and MP. It was a radical step towards formal education being made freely available to everyone for the first time. This Act is one of many educational firsts to have links with Haringey.

William E. Forster, MP (1818-1870)

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

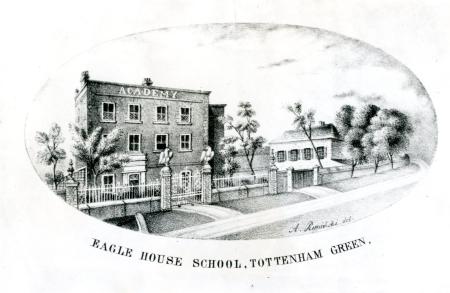

Forster’s family had long ties with Tottenham and educational reform, going back to 1752 when the Quaker, Josiah Forster (1693-1763), opened a school on the eastern side of Tottenham Green. The school continued after his death, by other members of the extended Forster family, and was eventually relocated across the other side of the Green at Eagle House – at the site where Tottenham Town Hall was later built. William Forster himself was educated at Grove House School, another Quaker-run school which was also on the Green, located where the College of Haringey, Enfield and North East London is today, and just next to where Eagle House (below) once stood.

Eagle House School on Tottenham Green, c.1854

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

Over the centuries, Haringey has been pivotal to educational innovation, reform and experimentation in this country. In 1673 Bathsua Makin, described as the most learned woman in the country at the time, published a book arguing for the education of women, and established a school for ‘gentlewomen’ at the High Cross, Tottenham. Makin tutored the daughter of Charles I - Princess Elizabeth. Her school’s syllabus was progressive – and subversive for some – advocating a practical, intellectual and moral training for her female students, which included grammar, logic, languages (she could herself speak over 6 languages!), mathematics, geography and the arts. This was an exceptionally wide and varied curriculum for the time, let alone for educating girls.

Bathsua Makin

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

From the 18th century, local Quaker schools also furthered the progressive and inclusive attitudes to education. Priscilla Wakefield 1751-1832, a well-connected and influential Quaker who lived in Tottenham, actively encouraged and assisted the economic emancipation of women through their education and learning.

Priscilla Wakefield

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

Tottenham, also had a number of boarding and alternative schools established there, catering for middle-class families who wanted an alternative grammar school education for their children. In 1827 Thomas Wright Hill (1763-1851) and his sons, Rowland, Matthew and Edwin, opened the progressive Bruce Castle School.

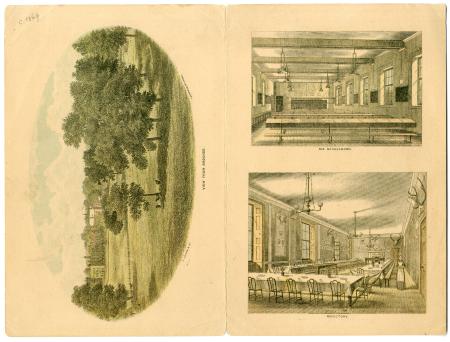

The Hills adopted a radical and experimental methods to schooling, with an enlightened syllabus and relaxed approach to discipline, with no corporal punishment – unusual for the time. They believed excessive punishments and rewards in school were not conducive to learning, and that good discipline is achieved by more subtle means.

Bruce Castle School brochure showing the Big Schoolroom (today’s Lecture Hall with its large windows we know so well), and the Refectory (nowadays the main Reception area and Gallery; the maid on the left just disappearing through a door, is where the main entrance door is today)

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

Up until 1870, formal education was available mainly to wealthy, middle or upper class families. Ragged Schools or schools run by charities and religious institutions usually taught the poor. There was a school of the Ragged School type in Tottenham between 1863-1880, known as the Union Sunday Evening School, running for a while from the Lancasterian School (itself another charitable school based on the Lancasterian system by Joseph Lancaster). One other notable charity school in Tottenham was the Blue or Bluecoat School which was based from 1735 on Scotland Green, (known as such because of the distinctive blue uniform originally worn by their pupils; it became known as the Middle Class School – and the building is still there today, and run as a pub called The Bluecoats).

In 1870, Forster’s Education Act made education compulsory for children aged between five and twelve years, and specified that schools were to be publicly funded. It did not make all education free or compulsory but did order, for the first time, that a school be placed in reach of every child.

By 1902 Local Authorities were responsible for elementary education and schools in the area. The former District Councils of Wood Green, Tottenham and Hornsey, all set up School Boards to manage elementary schools. Secondary schools were run by the County Borough of Middlesex. By 1906, schools not only educated pupils but also offered a supportive environment, with impoverished pupils being provided with school meals.

In 1921, Albert J. Lynch, Headmaster of West Green School, and later a Mayor of Tottenham, was equally experimental. He adopted an educational method called the Dalton Plan, and wrote a book on the topic as a reaction against the rigidity of the usual curriculum. Students could choose their own subjects and follow individual learning plans.

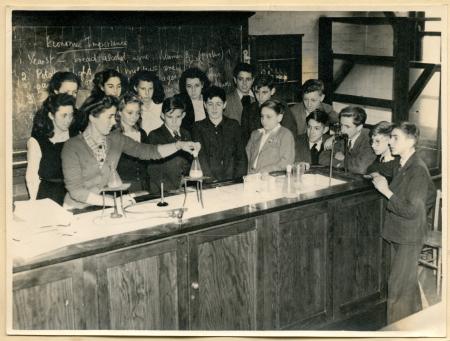

Hornsey County Grammar, science class c.1940s

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

During the 1960s, in protest against ‘banding’ in schools and the placing of African Caribbean children in schools for the ‘educationally sub-normal’, the poet, activist and educationalist John La Rose led at the forefront of the Black Education Movement. He founded the George Padmore Supplementary School in 1969 in Stroud Green, teaching subjects such as Pan-African history and culture, on top of the state schooling. Classes were designed not only to teach school syllabus, but also to build self-esteem and confidence of each student.

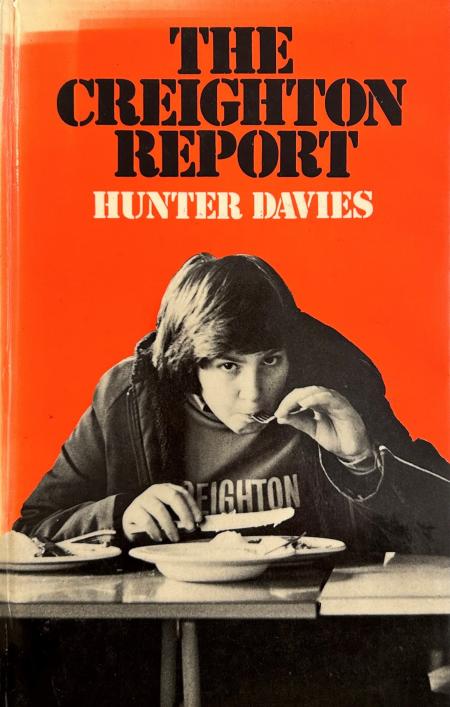

Creighton School (now Fortismere School) in Muswell Hill was the focus in the early 1970s for integrating African-Caribbean and other ethnic minority children into the school, bringing pupils from distant parts of Haringey. Led by the Headteacher Molly Hattersley, the purpose of the experiment was to try to maximise education choice and social interaction, giving each child the same educational opportunities.

Front Cover of 'The Creighton Report', 1976

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum

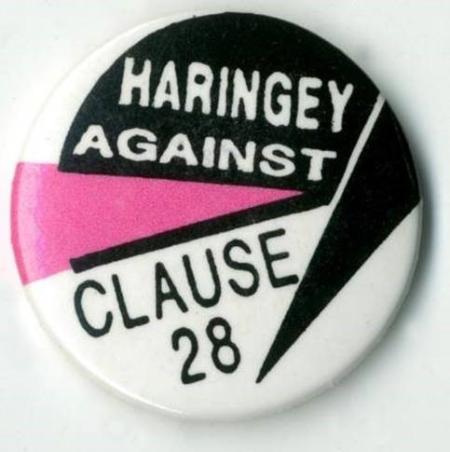

With widespread community protests and Bernie Grant being the first MP to voice opposition, Haringey was also central to the campaign against Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, which prohibited local authorities and schools from 'promoting' homosexuality. Bernie, as MP for Tottenham and a former leader of Haringey Council, identified the clause as an attack on the rights of a minority and argued for the need for schools to address the topic of homosexuality.

Haringey against clause 28 campaign badge

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum