Back in 2010 we held an exhibition at Bruce Castle that looked at people from Haringey who had worked at Royal Mail or had some links to the museum collections we hold about the postal service. Below are some reminiscences from some ex-postal workers from Haringey.

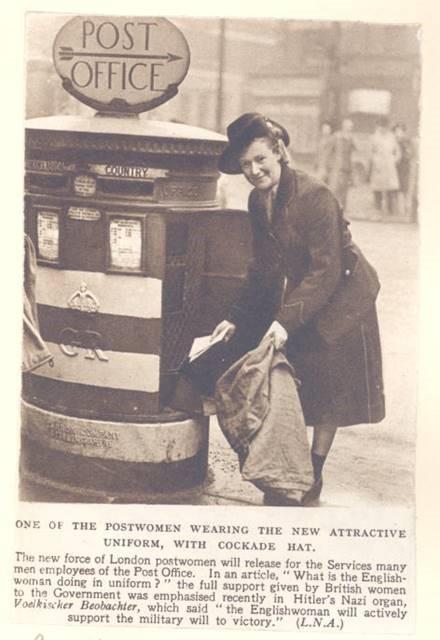

Alison Nunes came to Britain from Jamaica in 1964. She worked as a Postwoman and supervisor for the Royal Mail from 1967 until 1993. Here she talks about what they had to wear as a uniform in the late 1960s:

“All women working for the Post Office in my time were all measured for uniforms. When they arrived about one woman out of ten had a fit. Mine did not look anything so special even after they were remade. They were never comfortable to wear, being made of a coarse wool material. It was warm in winter but boiling hot in summer, until a cotton one was provided. Boots or shoes were unwearable. The mail pouch/bag full of mail and packets weighed 27lbs! A lot of what I did was enjoyable, and I met lots of people.”

Photograph of Alison Nunes

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

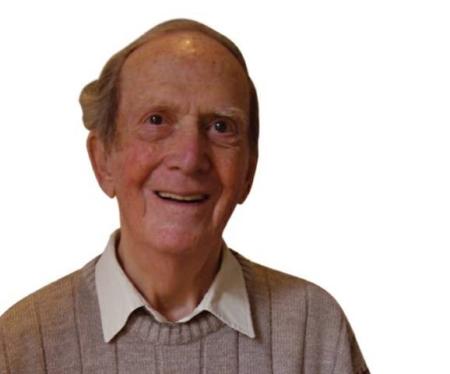

Les Rawle started in the Post Office as a messenger when he left school at 14 in 1939. After he was called up for the War, he returned to work as a sorting clerk in the North District Post Office. In 1948 he passed the exams to work at the counter. He remained working for the Post Office until his retirement. Les was looking at some of the telegrams that we have in the archive:

“Seeing these telegrams has brought back memories. During the 1950s I worked in the South Tottenham Post Office. The wooden counter was L-shaped and the bottom end was used for parcels. Beyond that a door into a room which had the tele-printers which received and sent the telegrams. Beyond that a further room where the Messengers sat before going out.

For telegrams, people paid you the money, so you stuck stamps to the value of that on the forms. The forms were in a box. They wrote their telegrams and brought it to the counter. You’d count the words. I think a minimum was 1/6d and then so much a word, stick the stamps on. Then I’d take it to the tele-printer room. You’d have to allow for those stamps when you cashed up.

Both men and girls worked in the tele-printer room. Holloway and Finsbury Park had a pipe system, compressed air tubes, which sent the telegram upstairs to the tele-printer room. At South Tottenham, there was a partition between the Post Office Room and the tele-printer room. There was an opening with a vee-shape in it, and you’d put the telegram form in there, and they’d see it or hear it, take it out and type it.

They were like large typewriters, electronic, with spools of white gummed tape and as the message appeared on the tape, they’d tear it off, stick it on a form, envelope it and the Messenger would take it out. For elsewhere in the country the tele-printer room would send it electronically to the Delivery Office nearest the address. “

Image of Tottenham resident, Les Rawle (1925-2012)

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

South Tottenham Post Office, on West Green Road, c.1939

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

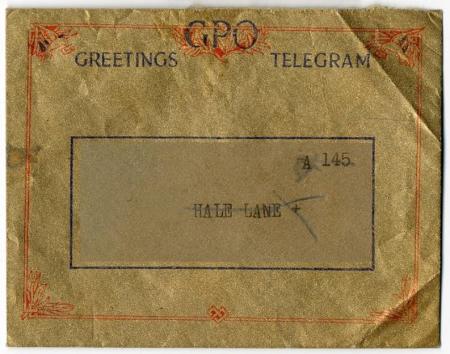

The telegrams Les refers to are part of a large Postal History Collection, which was deposited with Bruce Castle Museum in 1927. Originally collected by a telephone and post office worker, W V Morten, between the 1880s and 1923, the collection was put up for sale following his death in 1923. The Union of Postal Workers (now the Communication Workers’ Union) stepped in to save it for the Nation, purchasing it for £1592 15s 6d – quite a lot of money back then! As there was no national museum of postal history at that time, Bruce Castle was considered the most appropriate place to deposit the collection.

Telegram envelope from Postal History Collection, 1939

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

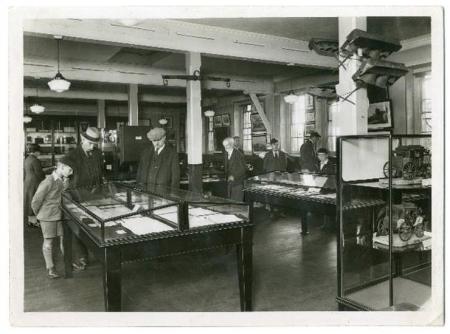

Postal History display at Bruce Castle Museum c.1931

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

So, why was Bruce Castle a suitable home for the collection?

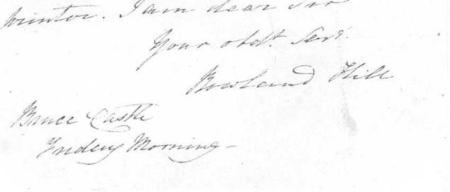

Rowland Hill the Postal Reformer

We’re lucky enough to have this collection at Bruce Castle all because of one man, the social, educational and postal reformer, Sir Rowland Hill, KCB, FRS (1795 –1879). Hill’s family purchased Bruce Castle in 1827 and the family opened a pioneering private boarding school for boys. They built the Victorian wing (on the West side of the building, extending into the park) to house the school dormitories and an additional classroom. Rowland Hill was joint headmaster with his brother Arthur. As a progressive school, the Hills did not approve of corporal punishment and so teachers would never hit the boys when they behaved badly - which was very unusual at the time. It was a popular educational establishment and boys came from around the world to Bruce Castle School.

Image of Sir Rowland Hill and his signature on a letter addressed from Bruce Castle.

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

While Rowland Hill was at Bruce Castle he began thinking about a comprehensive reform of the postal system. At that point, post was the primary mechanism for people to communicate by, but the services were not uniformly charged. Different private companies charged (sometimes) very expensive and varying amounts to send and deliver letters and parcels. Hill proposed a uniform cost for a set weight. In 1840 the Penny Post was launched where you could buy an adhesive stamp - first being the Penny Black - to indicate pre-payment of postage. Before this, postage was paid by the recipient of the mail, which meant if you couldn’t afford to pay the postage you didn’t receive your mail. Hill’s changes were a complete reform which made the postal system affordable for more people, and made it a more efficient, secure and reliable service. This was a world-first, the idea of which coming from within our very own Bruce Castle. Hill later served as a government postal official and was Knighted for his services to postal reform.

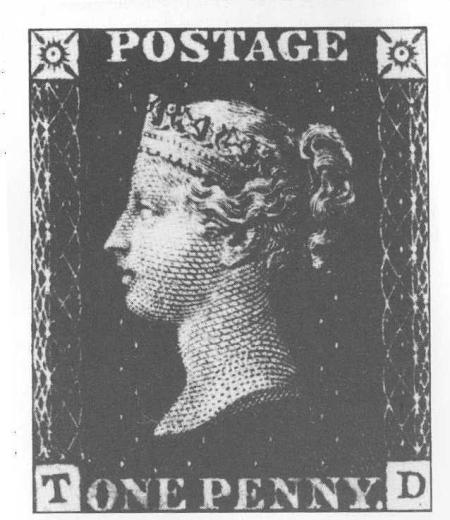

The Penny Black was first issued in the United Kingdom on 1 May 1840, but was not valid for use until 6 May. It featured a profile of Queen Victoria and this tradition of the contemporary Monarch’s profile being on UK stamps has continued through to today, although now a smaller image is usually in the top right corner of the stamp.

The Penny Black

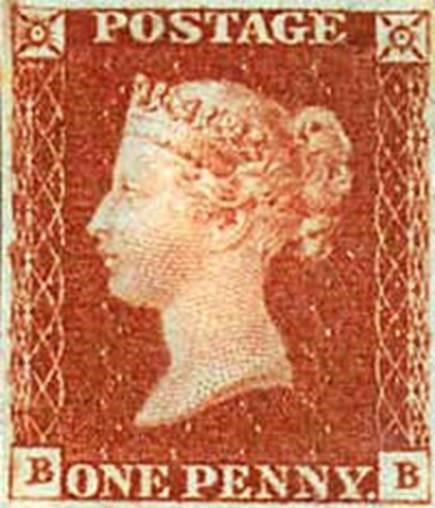

The Penny Black was a huge success, but had one particular flaw that meant a revised version was produced after a year in 1841. The Penny Red was issued because of the difficulty in seeing a black cancellation mark on the Penny Black – the cancellation mark stood out clearer against the red background. The Penny Red remained in circulation until 1879.

The Penny Red

For a more in-depth look at Sir Rowland Hill's Postal Reform and the history of the Penny Black have a look at Jack Zhang’s presentation on YouTube. This is the same presentation he did for us at the Local History Fair back in 2020, after much research in the Search Room at Bruce Castle for his book about Hill and the Penny Black. Thank you Jack!

Not all of Hill’s ideas were embraced by the public though. Richard West, a Fellow of the Royal Philatelic Society and a distinguished philatelist takes up the story:

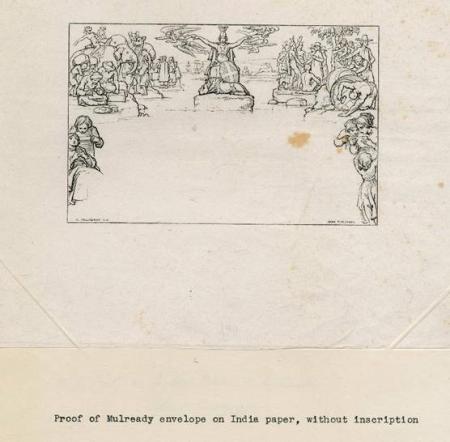

“Rowland Hill’s reforms of the postal system included not only the idea of cheaper postage, but also that the sender - rather than the recipient as hitherto - should pay the cost. Hill thought the public would prefer to use envelopes and lettersheets on which the postage was pre-paid. For these envelopes an illustration was designed by the artist William Mulready RA.

These items of stationery came into use on 6 May 1840. Their design however was quickly ridiculed by the public, which preferred the adhesive postage stamps - the Penny Black and Twopenny Blue had been introduced at the time. Many caricatures or lampoons were produced by stationery manufacturers whose livelihood was threatened by the new lettersheet.

Only six days after their introduction, on 12 May, Rowland Hill wrote in his journal: ‘I fear we shall have to substitute some other stamp for that design by Mulready the public have shown their disregard and even distaste for beauty.’”

Design for envelope illustrated and designed by the artist William Mulready RA. Which came into use on 6 May 1840.

From the collections and © Bruce Castle Museum & Archive

We agree with Hill, they were beautifully designed, and worked rather like the air-mail envelopes some of us might remember using, but with postage already paid. A rather good idea we think!

This British Pathé film, Postman’s Exhibition, from 1954 gives a wonderful trip back in time looking at Bruce Castle’s Post Office collections and the history of the postal service, all with the wonderfully clipped voice of the presenter! Some nice shots of Bruce Castle and the park too.

So, there we have the story of Haringey’s long and significant connection to postal services, not only through the forward-thinking reformer Rowland Hill, but through the people of Haringey working for the postal service today and in the past.